Bosnia - mines still kill February 2014

The house is small, cold and dark. A couch, dresser and some chairs fill up the largest room. Nahida, the mother puts down the glasses and pours sweet juice for the guests but can barely keep the tears away. Father Selmir holds up a framed photo and three-year-old Almedin kisses the photo of his big brother Sejdo who became ten years. It is only a few months since he died. The father and eldest son was on a day in January out picking metal residues in the forest to sell and get some money .

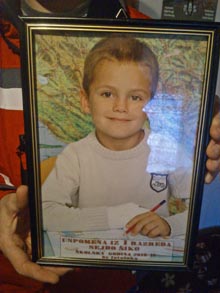

Sejdo, ten years old when he stepped on a mine and was killed.

-That day I brought my son Sejdo. He would sometimes come along when I collected metal to sell, there is the only opportunity we have to get some money, Selmir says.

-Suddenly I heard an explosion. Sejdo was two feet from me when he stepped on the mine with his right foot and was thrown over. He asked me: "Dad, did you get hurt?". I replied, "No, nothing happened to me, let me have a look at you" and when I looked, he had blood all over his chest. I took off his t-shirt and saw that a part of his left body at the stomach and hip had been ripped away.

Selmir carried his son to the car and drove as fast as possible to the hospital in the neighboring town Gra?anica but when he arrived his son was already dead .

The Šiko family in the small village of Pribava in northern Bosnia is one of the dozens affected by mine explosions in Bosnia. Since the war ended in September 1995, more than 600 people have been killed and twice as many injured, mostly difficult with amputations as results.

Aso Selmir was injured by the mine. He has nine pieces of shrapnel in both legs, constantly aching and preventing him from carrying anything or to walk far. It does not make it easier for him to support his family, which was even before next to impossible.

Selmir, nine shrapnel pieces in his legs which constantly ache. Nahida and Almedin.

-There's nothing, no jobs around here, except for odd jobs for a few days. I go to the authorities but they are highly reluctant to help us, either with work or any support. Here in Bosnia there is nothing, Selmir says.

The family lives in a small house, wedged in the back yard of a bigger one. They have some chickens and grow vegetables on a piece of land and will now get some financial help from an aid organization so that they can survive.

But nowadays Nahida is the one who has to chop wood and carry it in, Selmir is unable for that now, nor to collect metal parts of the forest. The mine explosion was totally unexpected. In Bosnia there is close to 10.000 marked areas contamined with personal mines but where Sejdo was killed was in a supposed safe area.

-People usually go there and collect and chop firewood. Had it been marked we'd never gone in there. No one would want to expose their children to such a risk, says Selmir.

After the end of the war, the various fighting groups handed in their maps of the areas where mines were laid out and an internationally funded program for mine clearance started that would have been ended five years ago. Then Bosnia would have been cleared from all mines. But the problem was that funding for the mine clearance program would gradually had been taken over by the Bosnian government. But lack of cooperation and corruption among the politicians from the various entities has crippled the country's governance. Investment and development has not materialized, and Bosnia has never been able to pay for the mine clearance.

a Bosnian flag hanging outside the parliament building, street sellers, Sarajevo

- There are still huge problems with landmines in Bosnia. The mined area is more than 1,200 square kilometers, says Saša Obradovic at BiH Mine Action Center in Sarajevo, the coordinating body for mine clearance in Bosnia , and continues:

- We now have a strategic plan to make the country cleared by 2019, but because we do not have any money, we will probably never be able to realize that goal.

The Mine Action Center is responsible for the marking of the mined areas, but poverty in Bosnia creates many problems.

-People steal the mine-warning signs. They are sold to metal dealers to earn some money. But every time someone steals those signs, we need to search and mark the whole area again and it costs us a lot of money, Saša Obradovic says.

The jeep drives in front of my car. The gravel road winds up higher and higher above Sarajevo. I pass some blown-up houses, ruins, and at the end of the road, on top of a hill, there are snow-capped mountains visible in the distance.

A group of men in blue uniforms and with heavy protective clothing stand and look at a map. The day's work is scheduled to be here above Vogošca.

-It's an area that remained after the war. Now the local council in Vogošca asked us to clear it, says Latif, head of the mine clearing team.

According to the mine maps there shall be fifty personnel mines laid out here, some of the estimated 120,000 mines that still are uncleared in Bosnia. Along the hills, sometimes as close from each other as a few hundred meters, run deep trenches. The old trenches show where the front lines were.

Trenches, sometimes as close to another as a few hundred meters.

Below the trenches thorny shrubs and small trees grow and along the edge of the bushes, aisles are marked out of yellow plastic strips, periodically with detours into the bushes. These are markings of where mines may be. I'm standing about ten meters away, wearing armor and a helmet and watch when Kenan Gluhovi? slowly sweeps a metal detector in front of him. At every beep, he must bend down and gently poke around with a small shovel to be able to pick up the object that caused the beep.

Kenan Gluhovic, mine clearer

-It is extremely difficult to search here, he says.

-There were fights all the time with shelling so everywhere there are metal shrapnel, Kenan Gluhovi?, who was himself a soldier in the Bosnian army, says.

Here above Vogošca, a dozen men are carefully searching and unearthing grenades, shrapnel , screws, beer cans, pieces of barbed wire, scraps and sometimes mines, out of the ground. It is gruesome and for a moment I'm thinking about how people without remorse can construct and use mines entirely of plastic so they will be impossible to clear, but quickly turn away those thoughts. Enough for me just to think about the thousands damaged and killed around the world every month.

In Bosnia there is an annual need of 40 million euros for mine clearing, but funds are missing. This minefield is to be cleared by the end of May but lack of resources makes that doubtful. Poverty and mines will remain in Bosnia for a long time to come, it seems.

-Our mine-clearing team will not meet the goal, but if we get more support and more personell, then maybe we can clear this area from the mines until that day, says Ljuca Ferhat, one of those who clear mines in Bosnia.

© Lennart Berggren / Axiom Film February 2014